When you think of women in tango, you are stepping into a narrative of transformation. It is a story that moves from the shadows of the arrabales to the center stage of the world, shifting from silence and constraint to artistic sovereignty.

For over a century, the history of women in tango has navigated a complex relationship with a genre born in the bustling port districts and margins of Buenos Aires. Tango emerged in a time and place—the tenements (conventillos) and brothels of the late 19th century—where women were undeniably present, yet often lacked artistic protagonism. In those early days, they were the subjects of the songs, the inspiration for the longing, and the partners in the dance halls, but they rarely held the pen or the baton.

Today, however, the landscape has shifted entirely. Female tango dancers, singers, and composers are no longer footnotes; they are the architects of the genre. Their journey is a testament to how passion and determination can reshape cultural traditions from within.

As we delve into this history, we will explore how women transitioned from being the “object” of the dance, tied to the stigma of its origins, to becoming its “subject.” From the rebellious voices of the 1930s to the leaders of the modern milonga, this is the story of how women claimed their place in the embrace.

The Early Days

To understand the evolution of women in tango, we must look at where it began: the margins of the Rio de la Plata in the late 19th century. Tango did not start in the glittering ballrooms we see today; it was born in the conventillos (tenements) and, quite significantly, in the brothels and bars where the working class and immigrants gathered.

In this environment, women were present, but they lacked artistic agency. The social norms of the time dictated that “decent” women of the upper and middle classes should not participate in this raw, developing expression. Therefore, the first female figures in tango were often women of the night, waitresses, or those living on the fringes of society. They were essential to the dance’s existence, without them, the embrace would not exist, yet they were often stigmatized, their participation viewed through a lens of morality rather than artistry.

In these early venues, the woman’s role was strictly defined: she was the follower. This was not just a mechanical instruction for the feet, but a reflection of the social hierarchy. She was there to be guided, to be held.

The Burden of the Lyrics: Saints or Sinners

For decades, tango lyrics were written almost exclusively by men, creating a narrative where women were viewed entirely through the male gaze. In the imaginary of the early 20th century, women in tango were typically cast in one of two rigid archetypes:

- The Saint: The suffering mother or the faithful girl waiting in the neighborhood (el barrio), representing purity and the past.

- The Percanta: The woman who “betrays” the man by leaving him or the neighborhood, often seeking a better life or seduced by the lights of the cabaret.

It would take decades for women to pick up the microphone and flip this script.

The Turning Point: From Muses to Icons

The arrival of the 1920s and the explosion of the Golden Age (1930s and 40s) brought a seismic shift. The radio, the cinema, and the professional stage gave women a platform, and they used it to break the mold. They stopped being merely the “muse” to become Icons.

Dancers Who Broke the Mold

In the dance halls, women began to professionalize their art. A prime example is Carmencita Calderón, a legendary figure who bridged the gap between the old orillero style and the stage. As the dance partner of El Cachafaz (one of tango’s most famous male dancers), she did something revolutionary: she legitimized the female dancer as a professional artist.

Voices of Rebellion: Singers and Composers

However, the loudest shattering of the glass ceiling came from the singers. The microphone became a weapon against the “saint or sinner” archetype.

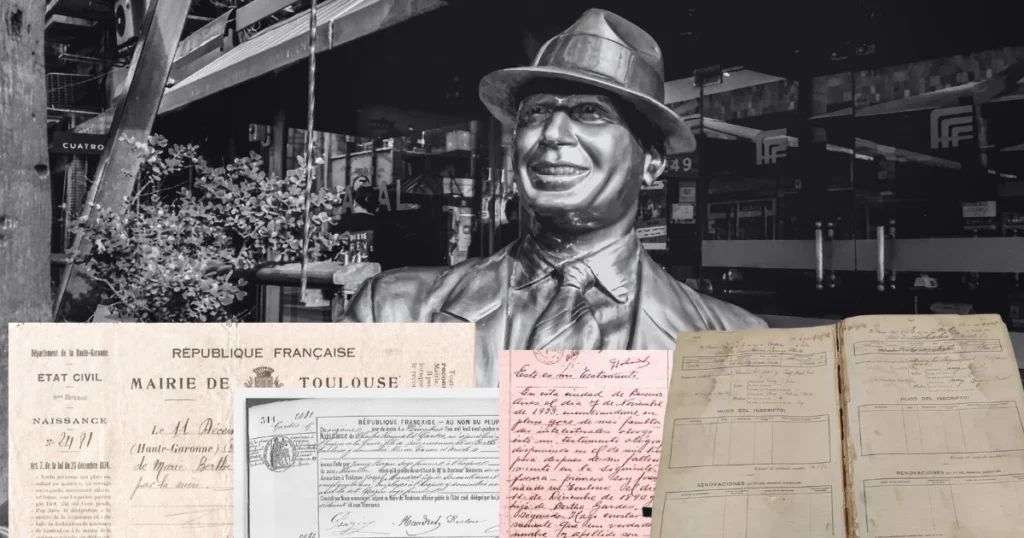

- Azucena Maizani: Perhaps the most visually transgressive figure of her time. Maizani famously performed dressed in traditional male gaucho attire. By wearing the pants—literally—she challenged the rigid gender norms of the era, claiming the raw, powerful emotion of tango for herself, independent of a male counterpart.

- Tita Merello: If other singers were polished divas, Tita was the reality of the streets. She was an actress and singer who embraced a “rea” (tough/streetwise). In songs like “Se dice de mí” (They Say About Me), she took ownership of the gossip and criticism leveled at women, turning it into an anthem of self-acceptance and strength. She wasn’t submissive; she was fierce, ironic, and undeniably human.

- Eladia Blázquez: Moving into the later decades, Eladia Blázquez proved that women were intellectual giants in composition. She shifted the focus of the lyrics from simple heartbreak to deep philosophy. With masterpieces like “Sueño de barrilete” and “El corazón al sur,” she showed that a women in tango could write just as poignantly as any man, earning her the title of the “Discépolo with skirts.”

Deserving life isn’t standing tall, far-off the evil, of failures. It’s like telling the truth, and our own freedom, you are welcomed!

Enduring and going by, gives us no right to brag, cause it isn’t the same living than honoring life!

Eladia Blázquez – “Honrar la vida”

The New Era: Sovereignty in Art and Embrace

If the the Golden Age was about emerging icons, the current era of tango is defined by artistic fullness. Today, walk into any tango show, festival, or milonga in Buenos Aires, and you will find women thriving in every role: as organizers, orchestra directors, instrumentalists, and composers. They are no longer the exception; they are a fundamental force driving the genre forward.

The Dance: Roles vs. Hierarchy

On the dance floor, the essence of tango remains a dialogue between two bodies. Yes, the structure of the dance still relies on distinct roles: one person leads, and one person follows. This mechanics is essential for the improvisation and the connection to work. However, the modern understanding of these roles has matured. Today, being a “follower” does not imply submission or passivity, nor does it reflect a social hierarchy outside the dance floor. It is an active, artistic role requiring immense sensitivity, musicality, and skill. The follower interprets the lead’s proposal and embellishes it, turning a suggestion into movement.

New Voices, New Stories

The most profound change, perhaps, is found in the music itself. The rigid lyrical archetypes of the “saintly mother” or the “treacherous woman” have largely faded into history. Contemporary female singers and composers are writing new chapters for the genre. They honor the classics but also bring their own realities to the repertoire. The lyrics sung by women today explore a vast range of human emotions.

From Muses to Creators

This shift marks the completion of a long journey. Women in tango have transitioned from being the passive inspiration, to becoming the creators of their own destiny within the genre. Whether it is a female bandoneon player leading a section in a top orchestra, or a dancer teaching a masterclass on technique, women today are not asking for permission. They are simply doing the work, driven by the same passion that ignited the genre over a century ago, ensuring that tango remains a living, breathing art form for everyone.

Where to See a Tango Show: Experience the Living Legacy

Reading about the evolution of tango is one thing; feeling its pulse in a room where the music breathes with you is another. If you are wondering where to see a tango show that witnesses the genre in its best form, you need to experience Secreto Tango Society.

Secreto brings together a world-class team where female artistry is not just present, but pivotal.

At the forefront is the powerful voice of Alicia Vignola. She doesn’t just sing lyrics; she channels the grit, the nostalgia, and a sweet yet rebellious tone that defined the history of women in tango. She captures the purest form of the art: emotional, unvarnished, and deeply moving.

On the dance floor, the narrative is carried by Estefanía Gómez. A 2019 World Tango Stage Champion, Estefanía is a dancer whose artistry has taken her around the globe. In the intimate setting of Secreto, her breathtaking precision and deep emotional connection are on full display.

One of the people guiding this entire immersive journey is Agustina Videla. As part of the Artistic Direction team, with over 25 years of experience and acclaimed works like the Social Tango Project, Agustina helps shape the night, blending movement, music, and light into a seamless journey of emotion. She is one of the architects behind the experience, ensuring that every note and every step lands directly in the heart of the audience.

In the close quarters of Secreto’s intimate venue, there is no distance between these artists and you. It is just the music, the passion, and the undeniable reality of tango living on in the present.

Ready to book and witness for yourself?

Women in Tango: their Own Story

The history of women in tango is no longer a sidebar in the genre’s biography; it is one of the main chapters. From the the early tenements and the “saints and sinners” of the lyrics, women have traveled a long road to claim their artistic sovereignty.

Today, they are the architects of the embrace and the voice of the melody. The passion, the resilience, and the sheer talent of female artists have ensured that tango remains a living, breathing art form, capable of reinventing itself without losing its roots.

Tango history is very interesting, and you can read a lot more about its revolution here. But, its legacy demands to be witnessed, felt, and heard in the first person. Book your tango night and check it for yourself!

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 5 / 5. Vote count: 3

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.